Exhibition review: Cosey, Basel, 12.11.2022–26.2.2023

Posted: January 29, 2023 Filed under: review | Tags: Basel, Cartoonmuseum, comics, Cosey, exhibition, French, museums, Swiss Leave a comment

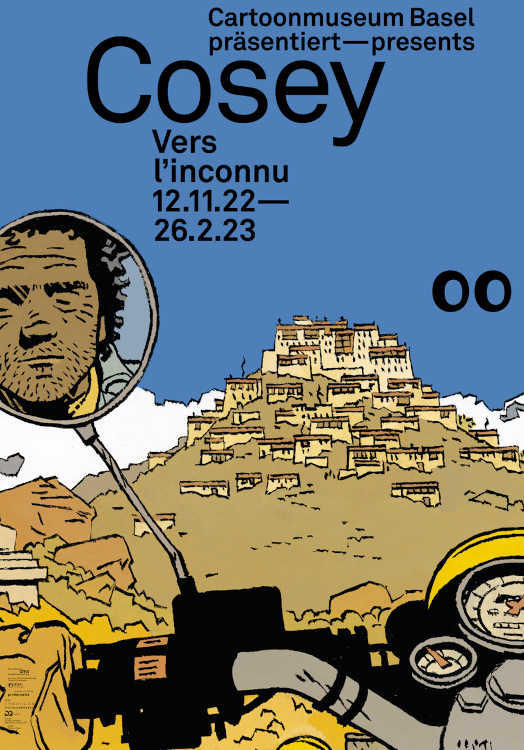

After Tardi and Joann Sfar, Cartoonmuseum Basel celebrates another Franco-Belgian master, albeit from Switzerland this time: Cosey (Bernard Cosendai), born in Lausanne in 1950 and above all famous for his long-running adventure series, Jonathan (1975–2021). Recently he attracted some renewed attention with his two Mickey Mouse tribute albums, and over the years he has also produced a number of standalone albums, e.g. In Search of Peter Pan. Accordingly, the exhibition devotes the most space to Jonathan, displaying many original drawings, and also some sketches and even artifacts that he collected from Tibet and other places where his comics are set.

For someone who has read Cosey’s comics only in translation, it is fascinating to see his hand-lettered speech balloons and title pages, and to realise what a skilled calligrapher he is. One of the downsides of this presentation of the original drawings, however, is that once more – as in the Tardi exhibition – no translations of the French text are provided.

The other, perhaps more lamentable, downside is that all the drawings show the pages after inking but before colouring. That is a pity, because (as the accompanying texts in the exhibition mention too) Cosey colours his comics himself and does so with considerable success, using a reduced palette to great effect. Only a single page is displayed with an overlayed colour cel, and there are also some watercolour sketches.

As usual, the artist’s published oeuvre can be perused in the museum library, where one can also watch a documentary film about him – alas, again, in French only.

Rating: ● ● ● ○ ○

Exhibition review: Manga – Reading the Flow, Zürich, 10.9.2021-30.1.2022

Posted: January 28, 2022 Filed under: review | Tags: Christina Plaka, comics, exhibition, manga, medieval Japan, museums, Swiss Leave a commentA very special manga exhibition is about to close soon: curated by none other than Japanese Studies professor Jaqueline Berndt, it may well be the most scholarly sound manga exhibition yet.

The special exhibition space at Museum Rietberg is basically one large room, divided into five partitions for this show. The first of these contains a reading area with a selection of manga tankōbon in both German and Japanese for visitors to peruse. The second section, titled “Panels – Pictorial Storytelling”, takes a closer look at how manga are made, in terms of both craftsmanship and layout. To this end, a manga has been purpose-made and is displayed in various stages of completion, including a video of the manga being drawn. The short manga in question was made by German mangaka Christina Plaka and is a present-day reimagining of the Japanese fable of the Poetry Contest of the Twelve Animals, which is shown in the exhibition as a 17th century picture scroll (in reproduction – apparently, the original scroll from the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin had been shown in another Japan-themed exhibition at Museum Rietberg which has already ended in December).

The following section, “Genres”, contains more pages of Plaka’s manga, but this time each double page is drawn in a different style that corresponds to the major manga demographics – seinen, shōnen and shōjo (setting aside the question of whether “genre” is the adequate term here). The fourth section is called “Studio” and invites visitors to continue Plaka’s manga story by drawing their own little yonkoma manga. Finally, there’s the “Genji” section which presents three different Japanese manga on the same topic – the 11th-century Tale of Genji – by means of enlarged reproduced pages with accompanying texts in German and English. These manga are Asakiyumemishi by Waki Yamato (1980), Ōzukami Genji monogatari Maro, n? by Yoshihiro Koizumi (2002), and Ii ne! Hikaru Genji-kun by est em (2015).

For the most part, the exhibition works fine and dandy. There are just a few points at which it perhaps oversimplifies things, or which for other reasons are not as convincing as they could have been. For instance, large parts of the exhibition rely on Christina Plaka’s Tanuki vs. Zodiac 12, i.e. a German manga, to explain things about Japanese comics. Of course, Plaka is an accomplished mangaka, and it would have been much more complicated to collaborate with a Japanese mangaka, translate the resulting manga, etc. But no matter how closely Plaka’s manga imitates Japanese manga, it can never fully replace the ‘real thing’. And when people come to the museum to learn something about how the Japanese make comics, they probably want to do so by looking at comics created by Japanese people.

Another somewhat problematic thing – not only about this but also some other manga shows in the past, e.g. Hokusai × Manga in Hamburg, or the more recent Rimpa feat. Manga in Munich – is how contemporary manga are forcibly connected to historical Japanese arts and culture, as in this case the Twelve Animals fable and the Tale of Genji. This carries the danger of perpetuating the myth that modern-day manga are direct descendants from such older Japanese arts. It may also give a false impression when manga as a whole are represented only by manga set in or otherwise concerned with Japanese history, when in fact there are only relatively few of those compared to present-day, futuristic or fantasy settings.

Lastly, the identification of manga as a necessarily participatory fan culture, as claimed by the “Studio” section, is a bit exaggerated. There is nothing wrong with including such an activity section where visitors can draw their own manga in an exhibition, but the accompanying text goes too far when it suggests that manga fandom with its fan art and fan fiction is not only an integral part but even “at the heart of manga culture” in Japan. While that is a common view, it is actually perfectly fine to regard the published manga independently from their readers (and vice versa). Also, not every single one of the millions of manga readers can be considered a ‘fan’, let alone one who creates fan art or fan fiction.

Speaking of the exhibition texts, it is a pity that no proper exhibition catalogue has been published, but at least the texts from the wall placards are collected in a free leaflet (both in German and English). It is available for download here: https://rietberg.ch/files/ausstellungen/2021/Manga/MuseumRietberg_Manga_Handout_EN.pdf

Exhibition review: Joe Sacco – Comics Journalist, Basel

Posted: January 16, 2016 Filed under: review | Tags: Basel, Cartoonmuseum, comics, exhibition, Joe Sacco, journalism, museums, Swiss, US 1 CommentSpeaking of Joe Sacco, there is a Sacco exhibition currently shown at Cartoonmuseum Basel until April 24. There is a lot to see there: the exhibition starts with original drawings from Sacco’s early comics, of which I found the juxtaposition of a “Zachary Mindbiscuit” story from 1987 and “More Women, More Children, More Quickly” from 1990 (both unpublished until the 2003 collection Notes From A Defeatist) the most interesting. While already an accomplished draughtsman in 1987, it wasn’t until “More Women…” that Sacco started positioning his caption boxes in oblique angles, which would become one of his trademarks.

Sacco’s main works, Palestine, Safe Area Goražde and Footnotes in Gaza, are all represented through original drawings (10 episodes from Palestine alone) as well. Another fascinating exhibit in this context is an arrangement of Sacco’s notebooks and reference photographs, next to the corresponding pages from the published comic. It becomes clear that while he gathered plenty of material, he took some liberties when it came to making a comic out of them – particularly in Footnotes, in which he re-imagines events that happened 50 years ago.

Insights into Sacco’s work process can be also gained from three short documentary films displayed on a screen (6 minutes in total), produced in 2011 by Portland Monthly and the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry: “Reporting from the field”, “Tools of the trade” and “Inspiration of Robert Crumb” (also available online). Another section of the exhibition traces the history of comics journalism before Sacco by way of “special artists” and reportage drawing from the 19th century on.

There is some more original art on display from Sacco’s more recent comics, which I’m not too crazy about. In the museum’s library, all of Sacco’s published works can be read in German and English. And then there’s another sensational exhibit: The Great War from 2013 (or 2014, according to the museum), in which Sacco tells the events of one day of a British military unit in WWI. The publication is subtitled An Illustrated Panorama, but I gather it comes in the form of a leporello (“accordion”) book. In the exhibition it is arranged in a semicircle. Not a comic, strictly speaking, but definitely an eye-catcher.

In an exhibition leaflet, Sacco is quoted (my translation): “Journalism is about countering the endless lies, even though it sometimes reiterates them – intentionally or unintentionally.” In this regard, journalism and scholarship are very much alike.

Exhibition review: The Adventures of the Ligne claire, Basel

Posted: January 16, 2014 Filed under: review | Tags: atom style, bandes dessinées, Basel, comics, Franco-Belgian, German, Hergé, ligne claire, museums, Swiss, webcomics Leave a commentThere is a lot to like about the exhibition The Adventures of the Ligne claire. The Herr G. & Co. Affair (German: “Die Abenteuer der Ligne claire. Der Fall Herr G. & Co.”), which can still be seen at Cartoonmuseum Basel until March 9, 2014. With a lot of original drawings and original editions, it shows what ligne claire (“clear line”) comics are and tells the story of the ligne claire style: from precursors such as Bringing Up Father and Bécassine, through Hergé and his contemporaries, to Joost Swarte coining the term “ligne claire” in 1977 and the ligne claire revival from the 1980s onwards.

There are only two things that the exhibition lacked:

Although some recent examples of ligne claire comics are exhibited (e.g. Christophe Badoux, Chris Ware), there is no mention of ligne claire webcomics – even though these exist, e.g. Tozo by David O’Connell, or The Rainbow Orchid (albeit that’s only an extensive preview to a printed comic) by Garen Ewing. The latter also interviewed the former once. It would have been interesting in the exhibition context to examine the clash of the new, online presentation format with the venerable drawing style.

My other minor complaint about the exhibition is that it mentions “André Franquin’s atom style” (or “atomic style”) as a comic style concurrent with ligne claire, without explaining what that atom style actually is. Some googling led me to Paul Gravett’s website, who has curated the exhibition In Search of the Atom Style in Brussels in 2009. He says, the atom style “seems to be less an artistic style to be adopted, and more an attitude, a state of mind, or as Swarte sees it, ‘… the taste for inventing things in a positive direction.'” – in other words, it’s more about which objects to depict, rather than how to depict them, thus similar to retro-futurism. Furthermore, the atom style appears to have been closely linked to the Marcinelle/Charleroi school (or is a revival thereof). “Atom style” (a term coined by Joost Swarte too) seems to be a difficult and vague stylistic designation at best, which makes it even more regrettable that the Basel exhibition uses it only offhandedly.